Nothing is as shameful in America’s history as the enslavement of and discrimination against African Americans. If you are not aware of how deep this stain runs in our history and how central it is to the American story, you may want to read Harvard Professor Jill Lapore’s history of the U.S., “These Truths.”

But at least twice, America has taken decisive actions to right some of the wrongs. The first was in the wake of the Civil War, when Congress passed the Civil Rights Acts of 1866 and 1871 and states ratified three constitutional amendments, the 13th, 14th and 15th that, on paper, ensured that African Americans would enjoy the rights that others had. The second was in 1964 and 1965, when Congress passed a landmark Civil Rights Act followed by a Voting Rights Act. Together, these laws demolished legal segregation and most of the barriers to voting that had been erected against black citizens in the South.

The stories behind these laws also offer us a lesson in how, with persistent activism and a rising tide of public opinion, governments can come to face major problems, build consensus around solutions, and move quickly and decisively—when the moment is right, the political will is strong, and the right leaders are in place.

But, first, a little history. For a 12-year period after the Civil War, the federal government took seriously its promises to protect African Americans in the South. During this period, 16 black men were elected to Congress from southern states, 600 or so were elected to state legislatures, and hundreds more held local office. Then, starting in the late 1870s, the federal government lost interest in enforcing what the Constitution promised. (For more about this tragic era, please see David Blight’s book, “Race and Reunion.”)

One by one, whites replaced blacks in Congress and state legislatures, and inside a few decades, all black legislators were gone and legal barriers erected to prevent African Americans from voting. At the same time, southern cities and states passed laws limiting social interaction between blacks and whites. This was segregation, and it prescribed things like separate restrooms in train stations, separate seating on buses and trains, separate water fountains, separate entrances to restaurants, and, of course, separate schools.

Most Americans knew of these injustices in the South and of similar unwritten practices in the North, and many deplored them. But there is a difference between a need you know about (a “should”) and one you feel compelled to act on (a “must”). And for many outside the South, including presidents and members of Congress, the oppression of others in a distant part of the country belonged in the first category, not the second.

What moved civil rights from “should” to “must,” starting in the 1950s, was the civil rights movement, which found ways of making the injustices apparent. The movement took many forms, from lawsuits (one of which ended in a historic U.S. Supreme Court decision declaring segregated schools unconstitutional) and rallies (such as the March on Washington in 1963) to actions that directly challenged discriminatory practices in the South. These direct challenges included the Freedom Rides, which targeted segregated accommodations in the South, and the lunch counter sit-ins that had young black students sitting at cafeteria counters in violation of segregation laws.

Still, through most of this, Congress refused to act. The reason: Southern states had senators and representatives in influential positions who made sure legislation was either watered down, as with the 1957 Civil Rights Act, or sidetracked.

The situation did not change until 1963, when President John F. Kennedy decided enough was enough. The outrageous actions of southern officials (the dogs and water cannons let loose on demonstrators in Birmingham, and Gov. George Wallace’s stand in the University of Alabama door, among them) finally forced President Kennedy to sponsor a meaningful civil rights bill. In one of the most eloquent presidential addresses ever broadcast, Kennedy outlined the need for a law that could ensure black citizens’ rights, not only in the South but everywhere.

But eloquence was one thing; the power of southern senators and representatives was another, and southern congressmen bottled up Kennedy’s bill in the summer of 1963. What happened next was a national tragedy that inadvertently resulted in a triumph. President Kennedy was killed in November 1963, and his successor, Lyndon B. Johnson, came to office with both the will and political skills to pass the civil rights legislation. In less than eight months, Johnson, a southerner, had wrestled the Civil Rights Act of 1964 through the House and Senate, breaking the longest filibuster in Senate history.

The bill was a sweeping package of legislation: It banned discrimination in education, employment, and “public accommodation,” which included restaurants, theaters, parks, courthouses, stores, and hotels, among others. In doing so, it struck down nearly every vestige of segregation in the South. As one writer put it, the law “reached far into the daily lives of southerners. . . . The past 50 years of American history are almost unimaginable without it.”

It included protections not only against discrimination on the basis of race and color but also religion, national origin, and gender. In 1986 the Supreme Court approved protections against sexual harassment, and in 2020 the court added protections against sexual-orientation discrimination—all from interpretations of the language in the 1964 Civil Rights Act. So, not only was the South in the 1960s changed by this act, life in America was changed as well. And it’s still changing our lives.

As sweeping as the Civil Rights Act was, though, it did not address one issue critical to African Americans: the right to vote and elect black public officials. Johnson had been reluctant to include voting rights in the 1964 bill because he thought it would cause southern senators and representatives to oppose it even more stubbornly than they did.

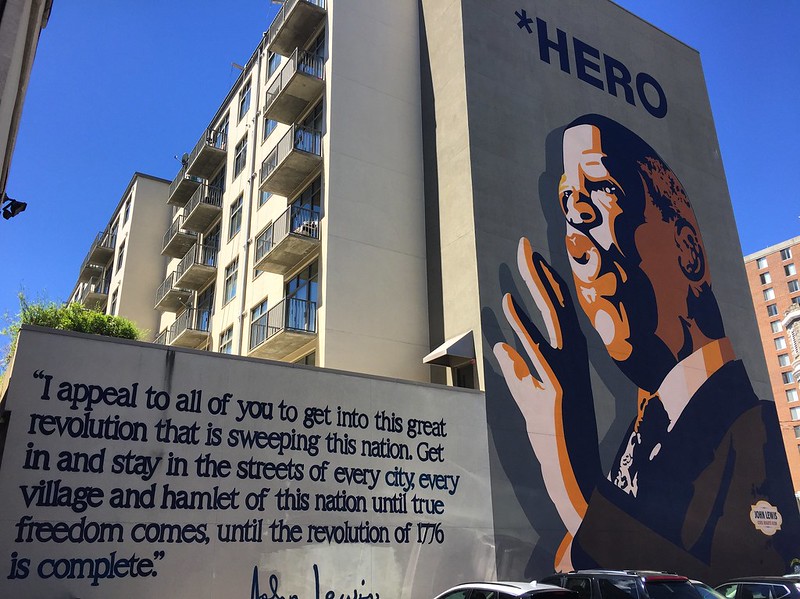

Once again, events forced a president’s hand. In this case, it was the “Bloody Sunday” incident in Selma, Alabama where state troopers waded into a peaceful march of protestors on March 7, 1965, beating them with nightsticks and leaving a future congressman, John Lewis, lying near the Edmund Pettus Bridge with a fractured skull. The nation was horrified by what it saw on television. So was President Johnson.

Eight days after Bloody Sunday, Johnson addressed a joint session of Congress, urging it to approve a bill mandating federal election supervision in states and localities with a history of voter suppression based on race. The bill passed both houses of Congress with large majorities and nearly unprecedented speed. Five months after Bloody Sunday, it was law.

The effect of the Voting Rights Act, like the Civil Rights Act, was immediate and profound. In Mississippi black voter registration went from seven percent in 1964 to 67 percent in five years’ time. Today in the South and across the country, African Americans vote in roughly the same percentages as whites.

Meanwhile the number of blacks in local, state and federal offices has soared. In 1965, there were six black U.S. representatives and no senators. Today blacks hold 52 House seats and three Senate seats. (Until his death in 2020, one long-serving representative was John Lewis, who was beaten severely on Bloody Sunday.) Three African Americans have served as governors since 1965; 17 have served as lieutenant governors. More than a third of America’s 100 largest cities currently have black mayors. (New York, Chicago and Los Angeles have all, at different times, had black mayors.) And, of course, Barack Obama was a two-term president of the United States.

In the end, the passage and enforcement of the Civil Rights Act and the Voting Rights Act contain two important lessons for us today. First lesson: Public opinion and political will often take a long, long time to build. And even as people and policymakers move from “should” to “must,” they require another ingredient for success, a leader with extraordinary political skills.

Second lesson: Once a democratically elected government does act decisively, it can overwhelm even the most entrenched forces of injustice, sweeping away legal and cultural walls built over many years. Government cannot change people’s hearts, but it can remove the barriers to those hearts being changed. And for this, we can thank government.

More information:

https://www.history.com/topics/black-history/civil-rights-act

https://www.britannica.com/event/Civil-Rights-Act-United-States-1964

https://www.history.com/topics/black-history/voting-rights-act

Give the credit to: federal government

Photo by anokarina licensed under Creative Commons.

[…] did the Americans with Disabilities Act come about? Much as the Civil Rights Act did, through a combination of persistent activism; a rising tide of public opinion; and enough […]