For most of human history diseases ravaged cities again and again, from the 14th century’s Black Death (a form of bubonic plague that wiped out a third of Europe’s population) to regular outbreaks of tuberculosis and cholera. The result: Urban living was at times nasty, brutish, and short.

What did governments do during these plagues? From the Middle Ages until the late 1800s some quarantined the infected and buried the dead, but otherwise governments acted like bystanders. Why? Public officials had no idea what caused epidemics.

This changed in the late 1800s with the development of germ theory and the growing knowledge among doctors and scientists of how infections were spread. Among the things they learned: Human waste and contaminated drinking water were major culprits in epidemics. These were things local governments could control—if they were willing to undertake massive investments in building water and sewer systems and in creating public sanitation department (that is, household trash collection).

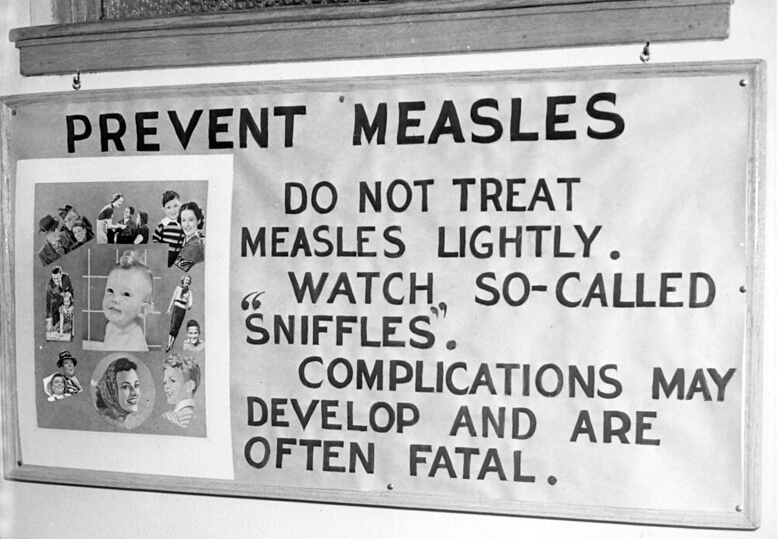

But that was only one role government played. Equally important was targeting the diseases themselves by financing research into how diseases were spread and into vaccines that could slow or stop epidemics. In the U.S., the federal government did the lion’s share of this work after the 1930s, but state and county health departments also played crucial roles by tracing outbreaks, building laboratories, working with local physicians, and organizing vaccination programs. Another major player: public schools, which required that children be vaccinated against an assortment of diseases, including measles, mumps, rubella, polio, diphtheria, tetanus, pertussis (whooping cough) and varicella (chickenpox).

The results? In a word, astonishing. Thanks to government research and vaccination programs, smallpox and polio—two of the greatest scourges of the early 20th century—were eliminated in the U.S. Measles was close to being eliminated before a recent wave caused by parents who refused to vaccinate their children. Even with some setbacks, most children today aren’t nearly as likely as their parents or grandparents to suffer with the mumps, measles, whooping cough, or chickenpox. (One example: From 1934 to 1943, nearly 31 million Americans, mostly small children, died of whooping cough. Today pertussis outbreaks are so rare and limited, most pediatricians have never heard of a death caused by this disease.)

As we know, new diseases do emerge from time to time, as AIDS did in the 1980s and Covid-19 in early 2020. When this happens, we expect the federal government and public health professionals in states and counties to search for treatments and make vaccines available. And sometimes government can move impressively fast in doing so. In a two-month period in 2020, Congress appropriated nearly $9 billion for coronavirus vaccine research, manufacturing, and distribution, with the hope for an early breakthrough.

If you’ve not had TB, smallpox, or polio, if you were vaccinated as a child before entering public school, if you live in a healthier environment than your great-grandparents could ever have imagined, if you have reasonable hopes for vaccines for AIDS or Covid-19, you can thank government for it.

More information:

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK218224/

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Public_health

https://www.nytimes.com/2020/07/15/sunday-review/coronavirus-history-pandemics.html

Give the credit to: local governments 30%, state governments 20%, federal government 50%

Photo by City of Minneapolis Archives. Licensed under Creative Commons.

[…] before the late 1800s could be nasty, brutish, and short, especially for the poor, who lived with recurring plagues and unbelievable stench. Trash was dumped in the streets along with horse droppings. Poor families […]