It’s not surprising there are things on which experts and average citizens disagree. After all, some things are not easily understood, like the need for deficit spending during recessions. But when it comes to the minimum wage, the citizens are of one mind: They like it and want it raised. It’s the experts who are divided.

We’ll get to the minimum wage’s popularity and the debates about it among economists. But first, a definition and a little history. The minimum wage is the amount workers must be paid by law for their hourly labor. It applies to most but not all workers. Among the exempt are some student workers and employees like waiters who routinely receive tips. There is also a list of occupations that, for one reason or other, are exempt, including newspaper delivery workers, seamen on foreign vessels, and babysitters.

The minimum wage is set at both the state and federal levels (and in some cases by cities). As a rule, employers are obligated to pay the highest amount in the jurisdiction where the work is done. So while the federal minimum wage is $7.25 an hour, nine states plus Washington D.C. have set theirs at $15. If you run a fast-food restaurant in Washington, then, you must pay your workers $15 an hour. Georgia’s minimum wage, $5.15, is actually below the federal minimum. Doesn’t matter. If you run a fast-food place in Savannah, you must pay $7.25 an hour.

How and when did we get a minimum wage? It came to us from abroad, then through the states and had to overcome major hurdles at the U.S. Supreme Court along the way. But once it was written into federal law in 1938 (when Congress set the first nationwide minimum wage at 25 cents an hour), public opinion was settled. People liked this idea.

New Zealand was the first country to have a minimum wage in 1894. Massachusetts was the first state to establish one in 1912. Other states followed. But the states hit a wall at the Supreme Court, which ruled in 1923 that minimum-wage laws at the state or federal levels violated employers’ and workers’ rights of contract.

Franklin Roosevelt tried to work around the court’s objections in 1933, when he convinced Congress to pass the National Industrial Recovery Act. It allowed industries to establish industrywide wages for themselves. For businesses not covered by these pacts, Roosevelt asked that they promise not to lower wages below $12 a week. (For a 40-hour week, that came to 30 cents an hour, although most workers in the 1930s worked longer than 40 hours a week.) If businesses made the pledge, they could display signs that had a blue eagle and the words, “We Do Our Part.” Two years later, the Supreme Court struck down this law, as well.

Then came the “big switch,” when the Supreme Court with new justices reversed itself in 1937 and upheld a state minimum wage. The following year, Congress passed the first federal law mandating hourly wages. And on a regular basis afterward, Congress raised the amount until it reached $1.60 per hour in 1968, or the equivalent of $11.53 today. This was the time, economists say, when the federal minimum wage reached its highest effective rate.

Over the next 50 years, Congress more or less lost interest in the minimum wage. Its last increase, to $7.25, came in 2009, based on a law passed two years before. For more than a decade, it has remained there.

But here’s where things have taken a surprising turn. While Congress lost interest in raising the minimum wage, states have taken it up. Today, 29 states plus the District of Columbia have minimum wages higher than the federal one. And according to the New York Times, if you averaged all those minimum wages (including some at the local level), the “effective” minimum wage was $11.80 in 2019, making it the highest minimum wage in American history.

And in raising wages, state legislatures have found a majority of citizens on their side. One poll in 2019 found two-thirds of Americans favored a minimum wage of $15 an hour.

So who doesn’t like the minimum wage? Some economists. They argue that raising wages by law disrupts labor markets and increases the price of goods and services. And in doing so, they say, it can cost some their jobs. The libertarian Cato Institute is typical of the conservative argument in calling the minimum wage “harmful.”

There’s just one problem with this: There’s little historical evidence that raising the minimum wage has actually caused significant unemployment. After all, the year when the federal minimum wage reached its highest effective level, 1968, was during a period of prosperity and low unemployment.

And then there are the larger working of economies. By paying people more, you put more money into the economy and, in doing so, create greater demand. Yes, a fast-food restaurant owner might try to get along with fewer workers as wages rise. But if her workers plus all those in businesses nearby suddenly have more money, it’s likely that demand will grow for hamburgers and french fries. And, pretty soon, she’ll have to hire back the old workers to keep pace with demand.

Finally, there’s a good likelihood that by raising the minimum wage, governments can reduce their own spending on things like food stamps and housing vouchers. In many communities, workers making $7.25 an hour cannot afford rent or food. Double their wages, and the need for government assistance goes down.

But the reason most citizens like the minimum wage likely has nothing to do with economics or government spending. It has to do with fairness. As they see it, if a person works 40 hours a week at a demanding job, he should earn more than $15,000 a year.

How much more? Depends on the community. The Massachusetts Institute of Technology has developed a helpful tool for calculating “living wages” (a wage that lifts a person out of poverty) by state and county. Here’s a hint: In Choctaw County, Alabama, a rural community 130 miles west of Montgomery, it’s $10.64 an hour or $22,124 a year for a single person with no dependents. Move that same person to Chicago and a living wage is $13.60 an hour or $28,280 a year. (Worth noting: The minimum wage in Illinois is $9.25 an hour. There is no minimum wage in Alabama.)

If you are one who believes people working at full-time jobs ought to make more than poverty wages, then you can thank governments for making the efforts they have. True, few states or localities mandate actual “living” wages for workers, but they do place a floor beneath employees’ wages. And as public demand for decent pay increases, there’s a chance that floor will rise. For that possibility, we can thank governments.

More information:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Minimum_wage_in_the_United_States

https://www.history.com/news/minimum-wage-america-timeline

https://www.theatlantic.com/ideas/archive/2021/01/counterintuitive-workings-minimum-wage/617861/

https://www.saturdayeveningpost.com/2020/08/a-brief-history-of-the-minimum-wage/

Give the credit to: local governments 10%, state governments 50%, federal government 40%

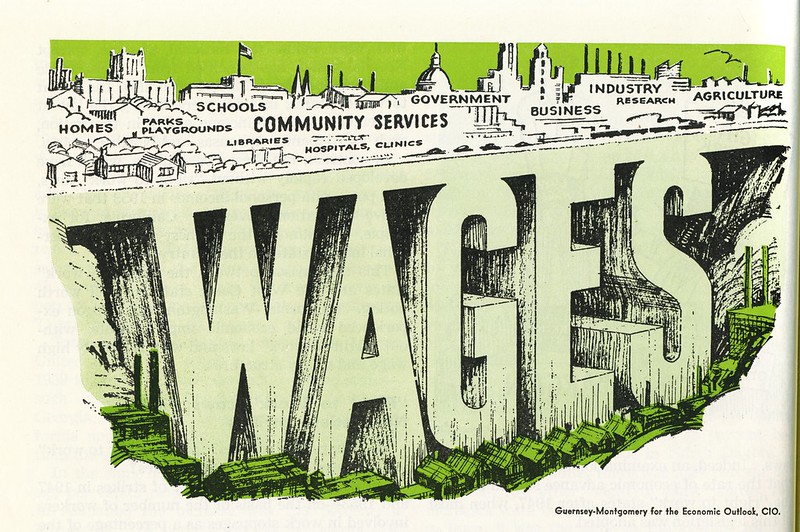

Illustration supplied by Tobias Higbie licensed under Creative Commons.

Leave a Reply