In early 2022, Warren Buffett, the renowned stock market investor and CEO of Berkshire Hathaway, wrote a letter to his company’s stockholders. Buffett’s annual letters are famous for branching off into essays on business conditions and current events once he has talked about his company’s performance. This time, one of the themes was that government functions as a “silent partner” to corporations. Had his company been located anywhere but America, Buffett wrote, “Berkshire should never have come close to being what it is today.” His advice to shareholders: “When you see the flag, say thanks.”

It was an interesting observation by a legendary Wall Street investor. But what did Buffett mean? How exactly do American governments help businesses?

We’ve written about some of the ways: through courts that mediate business disputes and interstate roads and railways that speed shipments, by insuring honest financial markets and sound banks so capital is available to invest, and by standing behind insurance companies that protect business activities. There’s more: Governments weed out shady competitors (through consumer product safety regulation, food and drug safety inspections, building codes, workplace safety measures, and cleaner air and water requirements) so honest businesses aren’t undercut by unscrupulous ones. They lower business costs by building and maintaining streets and roads and operating the Postal Service. The federal government makes sure nuclear power is available—clean and plentiful energy for powering businesses—by taking on the task of disposing of nuclear waste. And, of course, state governments provide a skilled workforce through public schools, state colleges and universities, and vocational education schools.

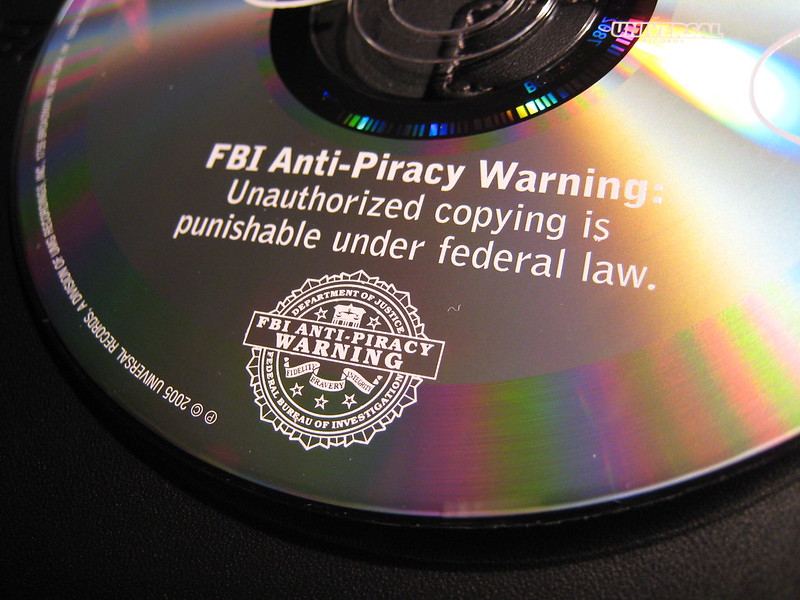

And here’s yet another critical service government provides for business: It issues and protects patents, copyrights, and trademarks. If it didn’t, business as we know it would cease to exist.

Why? Because two things are critical for businesses and especially for large corporations today: innovation and reputation. If a company invests millions of dollars in creating a new way of doing something valuable—say, a breakthrough in batteries that allows us to run electric cars hundreds of miles farther—it would do so only if it were sure no competitor could steal the innovation and sell it as its own. And what stops unscrupulous companies from stealing the innovations of others? Patents issued by the federal government (and national governments in other countries), and protected by the courts.

Reputation is also important to companies. There’s a reason you can’t start a soft-drink company and call it “Coca-Cola.” Or a fast-food place with large golden arches. Or a computer company with an apple as its logo. These names and symbols are protected as trademarks, also issued by the federal government and protected by courts. Turns out, images—names, symbols, logos, slogans—are central to creating customer loyalty. They tell customers the fizzy soft drink they’ve bought is . . . well, The Real Thing.

How did the federal government end up with the task of protecting intellectual property (which is the name lawyers use for copyright, patents, and trademarks)? Why did it do this? And how have these protections changed over time?

The Founders gave the task to the federal government by including copyrights and patents in the U.S. Constitution in Article 1, Section 8 under the “enumerated powers” of Congress. The section lists things Congress can do, from declaring wars and paying federal debts to establishing post offices. “Securing for limited times to authors and inventors the exclusive right to their respective writings and discoveries” is number eight in the list.

Congress wasted little time exercising these powers, passing the nation’s first patent law, signed by President George Washington in April 1790. Three months later the government issued its first patent, to Samuel Hopkins of Philadelphia, for a method of making potash, which is a chemical. (The first copyright law was passed in May 1790.)

Why did the Founders feel it was important for government to have a role in protecting copyrights and patents? For the same reason it was important for governments to protect other property rights—like your ownership of a car, a house, or a commercial property. These protections help ensure peace and prosperity.

In both physical and intellectual property disputes, the government’s first role is that of registrar. Your car’s title and your home’s deed are government documents showing you are their rightful owner. The same with a patent or copyright. (Biggest difference: You merely have to prove the car or house exists and that you own it to get a title or deed. To obtain a patent, you have to prove not only that it exists, but it does what you say it will do and is a substantial improvement over what existed before.)

Once a patent, copyright, or trademark is registered, the government’s role is protector. The courts can order compensation if someone publishes your book—or even large parts of it—without your permission. The same with trademark infringement. Using our trademarked slogan? Courts can order you to stop doing it and pay damages. Patent enforcement is slightly different because companies are allowed to sell similar products—you can’t patent car batteries, for instance, only the unique way your company made them last longer—so you have to show that someone used your unique process or product without permission.

What has changed over the years is that the definition of intellectual property has expanded beyond anything the Founders could have imagined. You can copyright not only books today but songs and movies; you can even copyright computer programs.

Patents, too, have expanded dramatically. In 1980 the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that bacteria created in a laboratory could be patented. The case concerned a bacterium developed by General Electric Co. that dissolved oil spills, but the ruling went far beyond that discovery. Some give the case credit for helping launch the biotech industry.

A second way the government’s role has changed: It has become the chief advocate for—and protector of—American intellectual property abroad. When Samuel Hopkins got his patent for potash in 1790, it protected his rights only in the United States. Canadians or Germans were free to steal his processes, and there was nothing Hopkins could do other than apply for patents in those countries. And if he did, why would Canada or Germany help a foreign inventor?

This wasn’t a major problem two centuries ago, when international commerce was limited, industrial progress slow, and manufactured goods large. The problem became noticeable with it involved something small and popular: books. The first great victim of copyright theft was Charles Dickens, the English author whose books were read as eagerly in the United States as in the United Kingdom. Only problem: Dickens got nothing for the sales of his books in the U.S.

When Dickens toured America in 1842 speaking to adoring audiences who had read these pirated books, he lashed into American publishers for stealing his works and urged the U.S. to adopt international copyright laws to stop the theft. The U.S. did strike reciprocal copyright treaties with other nations, starting in the 1890s, and eventually signed international agreements about patents that govern intellectual property to this day.

What do these international agreements mean? That companies in the U.S. can apply for patents and copyrights in other countries and be treated as if they were headquartered in those countries. (The same applies for foreign companies applying for intellectual property protection in the U.S.) And if someone infringes on a U.S. company’s patent in, say, India? The companies could seek a legal remedy—albeit from an Indian court.

But we know that despite these treaties some countries turn a blind eye toward patent and copyright infringement, especially if it involves a foreign company. And that’s where diplomacy becomes important. American companies cannot stand up to China, India, or Saudi Arabia, which regularly flout intellectual property rights. But the American government can.

In dealing with foreign governments that refuse to obey their promises, the federal government can levy sanctions, impose tariffs, even limit travel. And it can work with other nations to document the abuses and coordinate action. Increasingly, the federal government is doing these things to protect America’s intellectual property.

This, then, may explain why Warren Buffett called government his company’s “silent partner.” Only thing is, when it comes to protecting copyrights, patents, and trademarks, the federal government is not silent. Increasingly, it’s an advocate.

So when CEOs see the flag, the very least they can do is say, “Thanks for looking out for us.”

More information:

https://www.britannica.com/topic/patent

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_patent_law

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Trademark

Give the credit to: federal government

Photo by bizmac licensed under Creative Commons.

Leave a Reply